I was an ascetic—you turned me into a singer of songs;

You made me the leader of the revels and a seeker of wine.

I sat upon the prayer mat, dignified and grave;

You made me the plaything of the children of the street.

Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad of Tabriz (c. 1185–1248), commonly known as Shams Tabrizi, was a wandering mystic whose brief but incandescent encounter with Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī transformed the latter from a respected jurist into one of the greatest poets of love and divine union in world literature.

Who he was

A qalandar-like Sufi: unconventional, uncompromising, and deeply experiential rather than institutional.

Known for piercing speech, spiritual audacity, and a disdain for hollow piety.

Left few writings; his voice survives mainly through Rūmī’s poetry and later recollections (e.g., Maqālāt-e Shams).

His impact on Rumi

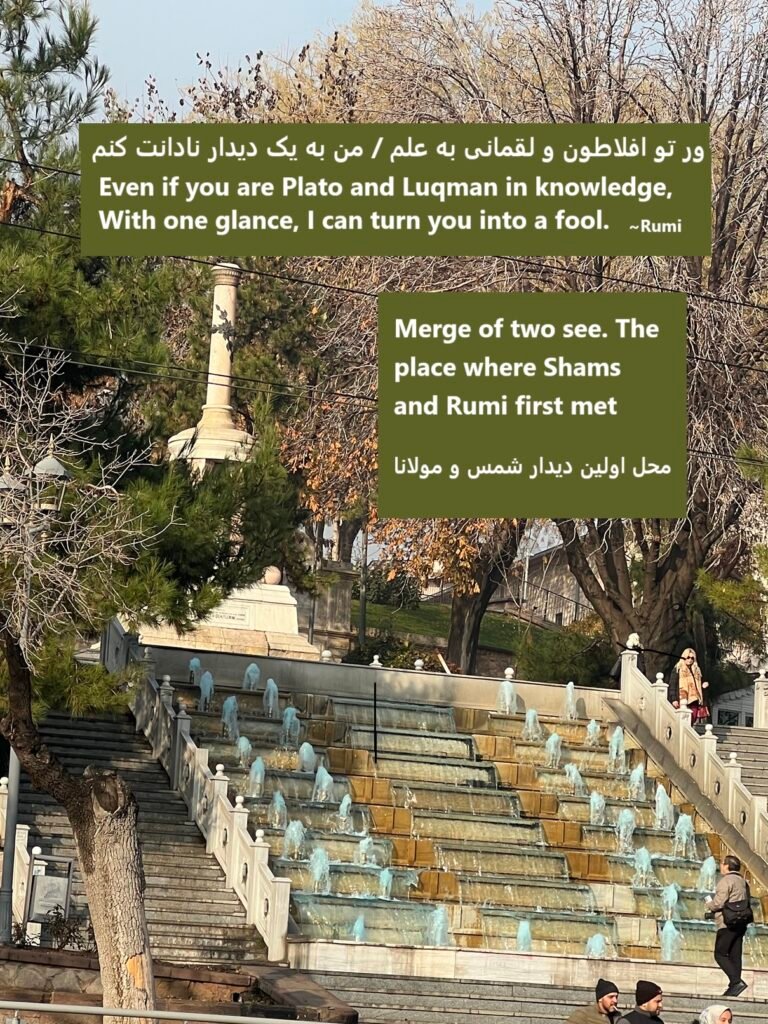

Their meeting in Konya (1244) ignited a radical inner transformation.

Shams became the mirror of annihilation (fanāʾ) through which Rumi tasted ecstatic love.

After Shams’s disappearance, Rumi poured his longing into verse—culminating in the Dīvān-e Shams-e Tabrīzī, named in Shams’s honor.

Core themes

Love as fire: burning away ego and duality.

Direct knowing over formality and status.

Light and presence: truth is tasted, not argued.

“Where there is ruin, there is hope for a treasure.” — attributed to Shams

Shams of Tabriz claims that he foresaw the meeting with Rumi—the most important event of Rumi’s life—in a dream. He states:

“I saw in a dream that they told me: ‘We shall place you in companionship with a saint.’

I said: ‘Where is that saint?’

They said: ‘He is in Rum… The time has not yet come! All matters are bound to their appointed times.’”

(Maqālāt of Shams of Tabriz, vol. 2, p. 162)

There is not much reliable information about the life and works of Shams of Tabriz, and it is unclear whether the collection of writings attributed to him truly belong to Shams himself.

The Book of Maqālāt of Shams (The Conversations of Shams of Tabriz)

Shams al-Din Tabrizi showed little interest in writing down his thoughts or poetry, and most of what has been preserved in his name has been transmitted through Rumi and other companions. Among the works attributed to him is the book Maqālāt of Shams. This book is a collection of sayings, poems, and captivating anecdotes spoken by Shams during his stay in Konya and written down by Rumi’s and Shams’s disciples and admirers. Initially, these sayings existed as scattered notes that were gradually and fragmentarily gathered into a single volume, which today is considered one of the important texts of mystical literature. According to Badi‘ al-Zaman Foruzanfar, the eminent Iranian scholar of Rumi, there is an undeniable connection between the Maqālāt of Shams and the Mathnavi-ye Ma‘navi, as though Rumi was profoundly influenced by Shams’s words and often composed his stories and parables inspired by them.

(Source: Ketabrah website)

It appears that the intention of the author or authors of the Maqālāt of Shams was to undermine the exalted spiritual station of Rumi by portraying him as a follower of a corrupt and egotistical individual who neither accepted God, nor the Qur’an, nor the Prophet Muhammad.

The following material is taken from wikitasavvof.com:

Shams described the Qur’an as follows:

“What is meant by the Book of God is not the written mushaf (the physical Qur’an), but rather that man who shows the way. He himself is the Book of God; he is the sign, and within that sign are many signs.”

(Halabi, Ali-Asghar, Foundations of Mysticism and the States of Mystics, p. 557)

In another passage, the master of the path considers the spiritual guide to be the alchemy of salvation rather than the Qur’an:

“Thus we realized that what delivers you is the servant of God, not that mere written text. Whoever follows the ink has gone astray.”

(Maqālāt of Shams of Tabriz, 2012, vol. 1, p. 316)

Elsewhere, he speaks of unbelief, heresy, and Islam:

“My joy lies in my unbelief, in my heresy; there is not much joy for me in my Islam.”

(Maqālāt of Shams of Tabriz, 1990, p. 144)

It is also claimed that Shams accuses Lady Fatimah (peace be upon her) of deficiency in spiritual knowledge, while regarding a woman such as Rābi‘a al-‘Adawiyya—despite her alleged immoral past—as a true mystic who should serve as a model for both men and women.

(Maqālāt of Shams of Tabriz, p. 343)

In the Maqālāt, Shams narrates an incident in which one of his students asks him for sexual relations. In explaining this episode, Shams says:

“Desire in me had so completely died that that organ had withered away, and all lust had withdrawn from it. Then I saw in a dream that I was told: ‘Your self has a right over you.’ Give it its due. Thus, in obedience to God’s command, Shams went in search of a handsome youth and spent the night with him.”

(Maqālāt of Shams of Tabriz, p. 109)

Another example of Shams’s attraction to handsome youths is his request to Rumi, expressed as: “I want a lovely young witness,” asking him for a good-looking adolescent. Rumi is said to have offered his son, Sultan Walad—known for his beauty as the “Joseph of the age.”

(Jami, Nafahat al-Uns, p. 538; Aflaki, Manaqib al-‘Arifin, vol. 2, p. 622)

Shams, in addition to his harsh and biting language and extremely rough temperament, is also reported to have used obscene expressions. Some of his words dealt explicitly with sexual matters, portraying him as an indecent and ill-mannered individual:

“He said: ‘So-and-so came from a distant journey, having heard of such-and-such a shaykh. When he arrived, the shaykh asked him, “What did you come seeking?” He replied, “I came seeking God.” The shaykh said, “God…” and made an obscene gesture toward someone. “That was it—go back.”’”

(Maqālāt of Shams of Tabriz, 2006, p. 95)

He is described as being so shameless and indecent that he would even disclose the most intimate sexual secrets to others.

(Maqālāt of Shams of Tabriz, p. 869)

According to these accounts, such behavior was not limited to private storytelling; it is alleged that he even engaged in amorous acts publicly, without concern that others might witness them.

(End of material from wikitasavvof.com)

As stated, the authors of these Maqālāt are unknown, and some of the material is considered fabricated, written solely to tarnish the moral character of Rumi.

Throughout history, many religious scholars and authorities, in order to preserve their own status, either killed those who thought differently or sought to destroy their reputations through false accusations. Although lying is considered a major sin in Islam, such falsehoods were repeated from various sources until many people accepted them as truth.

It is narrated from Imam Zayn al-‘Abidin (peace be upon him):

“Avoid lying, whether small or great, in seriousness or in jest; for when a person lies in small matters, he dares to lie in greater ones.”

(Tuhaf al-‘Uqul, p. 278)

Considering the conditions of the Middle Ages and the religious fanaticism of that era, and taking into account the beliefs attributed in the Maqālāt of Shams, both Shams and Rumi—who was regarded as his follower—would have been labeled atheists, heretics, irreligious, apostates, polytheists, and deviants, crimes for which the punishment was death. No one would have followed such a person who openly taught such beliefs—yet we know that both had many followers.

Therefore, these Maqālāt cannot be regarded as reliable historical documents. Most importantly, in all of Rumi’s authentic works, not only do we find no such deviations, but rather an abundance of reverence, humility, and self-effacement before God, the Holy Qur’an, and the Prophet Muhammad.

The use of extremely coarse language in the Mathnavi may astonish modern readers—words that even common people today consider vulgar. However, at that time such expressions were part of the prevailing culture and were not regarded as especially offensive.

It was Rumi who made Shams known; it is possible that others later adopted the title “Shams” to benefit from his fame and mystical reputation. The fate of Shams himself is uncertain. Some believe he withdrew into seclusion; others claim he was killed by Rumi’s disciples, who deeply resented him, and thrown into a well outside Konya. Another group believes he returned to his birthplace, Tabriz, and died there. Today, two tombs are attributed to him—one in Khoy and another in Turkey—both surrounded by doubt and serving as sources of income for their custodians. Recently, it has even been claimed that there is a third tomb attributed to Shams in Pakistan.

Mohammad Ali Movahhed, a prominent scholar of mysticism, believes that the site near the city of Khoy known as the Minaret of Shams of Tabriz, which has great antiquity, is his true resting place. However, other eminent scholars such as Badi‘ al-Zaman Foruzanfar and Mohammad Ali Tarbiyat do not agree with this view. Franklin D. Lewis, a leading Rumi scholar, although uncertain about Khoy as Shams’s burial site, considers it—based on available evidence—to have been Shams’s final place of residence.

Some even believe that Shams never had a physical existence and appeared to Rumi only in dreams, like an angel appearing to the Prophet Daniel to foretell future events.

Remember, O heart, what dream you saw last night,

For the morning of good fortune opened a door for me.

Perhaps I saw in a dream that the moon lifted me,

Carried me up to the heavens, and set me upon the sky.

In sleep, revelation comes to him.

With eyes closed, you behold forms in sleep;

When the eyes open, the veil of that vision is lifted.

Be silent, so that you may hear the revelations of Truth,

For spoken revelation is a hundred thousand lives.

In sleep, when the eye of the body rests, with the eye of the heart and soul he reads the Eternal Tablet.

Sleep comes to seize your reason away;

How could the madman sleep—what does he know of night?

In the creed of the madman there is neither day nor night;

What he possesses—he alone knows, he alone knows.

From the turning of the heavens, this world gained day and night;

The madman knows that realm—he sees the heavens themselves.

If the eye of his head sleeps, without a head he is all eye,

For from the vision of his soul he reads the Eternal Tablet.

Become a night-traveler, a bold wanderer in love,

So that a task may be undone by that lock which scatters its curls.

The madman is of another kind—he carries the soul within;

His eyes are fixed on the Beloved, his burden is no longer his own.

If you seek further explanation—from Shams of Truth and sovereignty,

Know that Tabriz illumines the whole world with ever-new light.

The author believes that this interpretation appears more logical for several reasons:

Rumi, despite having countless followers because of his knowledge and mysticism, regarded himself as nothing in comparison to Shams. He revered him and saw himself completely as his disciple.

O exalted God—Shams al-Din of Tabriz, from him the soul of the earth!

Radiant as the settled Throne, whose light made even the lights envious.

O countless blessings upon the most auspicious hour,

For in that moment Gabriel unveils those mysteries.

According to this understanding, when Rumi’s followers saw that their master considered his own knowledge insignificant compared to that of Shams, they should all have become devoted disciples of Shams, preserving and spreading his works and writings. In that case, Shams would today be more renowned and beloved than Rumi. Instead, we see hostility toward him—so intense that it went as far as attempts on his life—forcing Shams to leave Konya twice.

Rumi even attributes to Shams a station higher than that of the prophets of the past, at times calling him “my Shams and my God” or “Shams al-Ḥaqq (the Sun of Truth),” for example:

Lay that head down before Shams of Tabriz,

For faith itself is the prostration before that idol.

You are the Ka‘bah of lovers, O Shams al-Ḥaqq of Tabriz;

From your Zamzam flows sugar-sweet water, O beloved.

Rumi calls himself the moon that becomes luminous through the light of Shams, the sun:

Shams of Tabriz is more renowned than the sun;

I, who am a neighbor to Shams, am famed like the moon.

He regards Shams as God:

My elder and my guide, my pain and my remedy—

I speak it openly: you are my Shams and my God.

I have reached Truth through repentance; O you who render Truth its due,

I have offered thanks to you—my Shams and my God.

I am undone by love for you, for you are the king of both worlds;

So long as you cast your glance upon me—my Shams and my God.

I am effaced before you until no trace of me remains;

Such is the rule of courtesy—my Shams and my God.

Your monastery is my Ka‘bah, your hell my paradise;

You are the companion of my days—my Shams and my God.

Or again:

O Lord Shams al-Din, from the fire of separation from you,

Even the everlasting light grows envious—praise be to this flame.

Rumi is ashamed to call him human, and he fears God to call him God:

Out of love I am ashamed to call him human;

I fear God if I should call him God.

Shams is the one who speaks upon Mount Sinai:

Mount Sinai of Moses was bloodied time and again in the passion of love,

For from the Lord Shams al-Din a voice falls upon the Mount.

He is the Christ of the age:

From separation from Shams al-Din I have fallen into constraint;

He is the Christ of the age, and the pain of my eyes has no cure.

Shams al-Ḥaqq of Tabriz entered love as Christ;

Whoever bears from him the Christian cord—let him tear it away.

One with such attributes cannot be an ordinary human being. He is one whose perfection completes creation:

Reveal, O Shams of Tabriz, a perfection,

So that no deficiency may remain in the “Be!” and it is.

The following materials, taken from the free encyclopedia Wikipedia, indicate that Shams regarded himself as superior even to the Prophet Muhammad (the Messenger of God) and the Holy Qur’an.

Shams’s Claimed Independence from the Prophet of Islam

In another statement, Shams of Tabriz presents himself as independent of the Prophet of Islam, saying that if he shows reverence toward the Prophet, it is out of brotherhood rather than need or dependence.

Elsewhere, with striking arrogance and pride, he describes his relationship with the Prophet of Islam in a manner that suggests Shams considers himself to be of equal rank and station. He states:

“I have a rein that no one has the courage to take hold of—except Muhammad, the Messenger of God. Even he takes hold of my rein only when I become fierce and the pride of dervishhood enters my head; otherwise, he would never take my rein.”

(Azad, n.d.)“Reciting the Qur’an Darkens Me”

In another key statement, Shams emphasizes that the Qur’an brings him no benefit and that reciting its verses only makes him darker:

“The treatise of Muhammad, the Messenger of God, is of no use to me. I need my own treatise. If I were to read a thousand [other] treatises, I would only become darker.”

(Azad, n.d.)

“God greets me ten times; I do not respond and make myself deaf.”

(Maqālāt of Shams of Tabriz, 1998 ed., p. 273)

Shams even insults Lady al-Ṣiddīqah al-Ṭāhirah (Fāṭimah, peace be upon her) and accuses her of deficiency in spiritual knowledge:

“Nothing comes of a shaykh from a woman… If Fāṭimah or ‘Ā’ishah had been shaykhs, I would have lost faith in the Messenger [peace be upon him and his family]—but they were not. If God were to open a door for a woman, she would still remain silent and concealed. For a woman, her spindle and her work are enough.”

(Maqālāt of Shams of Tabriz, vol. 2, pp. 157–158)

It can be stated with confidence that Rumi, more than any other poet-mystic, was influenced by the Qur’an in his poetry, and the seeking of grace from the words of the Qur’an is evident throughout all of his works.

Know that the words of the Qur’an have an outward form;

Beneath that outward form lies a mighty inner meaning.

O son, do not look upon the Qur’an only in its outward sense;

The devil sees in Adam nothing but clay.

The outward form of the Qur’an is like the human body:

Its features are visible, but its soul is hidden.

Rumi repeatedly expresses his devotion in his poetry to the Messenger of God, whom he calls the “Universal Intellect” (‘Aql-e Koll) and “Mercy to the worlds” (Raḥmatan lil-‘Ālamīn).

O Universal Intellect, master of countless arts, teach one enchantment,

That from it, within, a tender mercy may arise for the beloved.

From the light of the Universal Intellect my reason became so dazed and bewildered

That from it opium, hashish, and sweet wine were all dismissed.

Regarding “Mercy to the worlds,” he says:

From the heavens, in every sustenance, a call comes from the exalted ones:

O pure spirit, O leader—O Mercy to the worlds!

O Sana’i, go seek help from the soul of Mustafa,

For Mustafa came only as a Mercy to the worlds.

Likewise, in Majāles-e Sab‘eh (The Seven Sermons), Sermon One:

“O Messenger of God, O solver of the difficulties of the people of heaven and earth, O Mercy to the worlds—solve our difficulty, for today You are the solver of the difficulties of the people of heaven and earth.”

He calls the Prophet Muhammad the pride of the world:

The fortune of our youth is our companion; giving our lives is our task;

The leader of our caravan, the pride of the world, is Mustafa.

Therefore, Rumi cannot be the disciple of someone who considers himself superior to the Messenger of God and the Qur’an. Undoubtedly, Shams is a spiritual reality with whom Rumi is connected in the realm of unveiling and mystical vision, and Rumi sees himself as incapable of fully comprehending him.

Though Shams of Tabriz turns his back toward us,

A hundred thousand blessings be upon his path.

From Rumi’s perspective, Shams is “something else.”

O soul annihilated in love—you are something else;

O you who possess “that”—you are something else.

The secrets of the heavens and the states of this and that,

You read from the unwritten Tablet—and you are something else.

Some examples of Rumi’s descriptions of Shams in his poetry:

Blessed is that joyful bird who found a station in love;

Who finds a dwelling on Mount Qāf except the Simurgh?

Blessed is that divine Simurgh, the king—Shams of Tabriz,

Who is a sun neither of East nor West nor bound to any place.

They asked: “What did you see from Shams al-Ḥaqq of Tabriz?”

We said: “From that light, this vision fell upon us.”

Here he grants him a prophetic station whose rank is so exalted that even Gabriel, the angel of revelation, has no place before him:

The sovereign of the spirit, Shams al-Din—by the greatness of his elevation,

Gabriel of revelation does not know where to seat himself.

On that day when the call of Truth arose in the world of “Am I not?”

Give Tabriz, from the beginning, those who said “Yes” to that primordial covenant.

This is a reference to Surah al-A‘rāf (7), verse 172, which states:

“Am I not your Lord?” They said: “Yes, indeed.”

By the terms “sun” and “moon,” mentioned in the writings of the Prophets of God, is not meant solely the sun and moon of the visible universe. Nay rather, manifold are the meanings they have intended for these terms. In every instance they have attached to them a particular significance. Thus, by the “sun” in one sense is meant those Suns of Truth Who rise from the dayspring of ancient glory, and fill the world with a liberal effusion of grace from on high. These Suns of Truth are the universal Manifestations of God in the worlds of His attributes and names. Even as the visible sun that assisteth, as decreed by God, the true One, the Adored, in the development of all earthly things, such as the trees, the fruits, and colors thereof, the minerals of the earth, and all that may be witnessed in the world of creation, so do the divine Luminaries, by their loving care and educative influence, cause the trees of divine unity, the fruits of His oneness, the leaves of detachment, the blossoms of knowledge and certitude, and the myrtles of wisdom and utterance, to exist and be made manifest.(The Kitáb-i-Íqán)www.bahai.org/r/858099620

And to make pilgrimage to Shams, one must ascend as the Prophet Muhammad did—from al-Masjid al-Aqsa to the Mi‘raj.

O my noble master, Shams-e-Din, from your majesty, O Trustworthy Spirit,

From Tabriz, like the firmly established Throne, come forth from al-Masjid al-Aqsa.

Shams and the East (Mashriq) are used in the Holy Qur’an and in the works of Rumi as symbols of the ظهور (advent) of divine messengers who educate and refine humanity.

Every particle laughs in the splendor of that Shams al-Duḥā;

The particles receive their teaching from that radiant, gracious sun.

Shams-e-Haqq Tabrizi speaks to the bud of the heart:

When your eye opens, you will become a true seer with us.

In the opinion of the author, the meaning of “Shams” in Rumi’s poetry refers to the Blessed Beauty, and the mission of Bahá’u’lláh began in Tabriz after the martyrdom of the Báb, although He formally declared His mission in Baghdad.

That sweet-scented gazelle set out toward Tabriz;

Baghdad illuminated the world with insight.

When I traveled with Tabriz, I asked of Shams-e-Din,

About that mystery through which I beheld the creation of all forms.

Out of fear for his life, Rumi lacked the courage to openly state his name and identity:

“I have not the boldness to say who that person is.”

If we do not utter the name, nor give the sign,

The glass of the soul will still be shattered by this wine.

Do not seek sedition, turmoil, and bloodshed;

Speak no more of Shams of Tabriz.

Rumi also addresses Shams Tabrizi by other names and titles:

Ocean of Mercy, Sun of Grace, Mighty King, King of the Kings of the Spirit, and Pure Light.

“The story of Shams Tabrizi’s life is not entirely clear to us, as he spent most of his days traveling. Shams is believed to have been born in Tabriz. For many years, Tabriz was a center for Sufis and great thinkers such as Ahmad Ghazali, Najm al-Din Kubra, and Abu Najib Suhrawardi. Thus, from childhood, Shams became familiar with the works and ideas of these figures and followed Suhrawardi in some matters. Very little documentation exists about Shams Tabrizi; among them are the Ibtidā-nāmeh by Sultan Walad and the book Maqālāt-e Shams, attributed to Shams himself. However, even the Maqālāt—one of the ancient texts of Persian literature—does not greatly assist us in fully understanding Shams Tabrizi.”

The Book “The Path of Life” and download of the best books of Shams Tabrizi

It was Shams who taught Rumi silence—one of the stages of mysticism—and perhaps it was this silence learned from Shams that led Rumi to choose the pen name Khāmūsh (“the Silent One”) for himself.