It is the Light of God that sets the particles

Dancing—free of rank, possessions, or worldly claim.

Dance in this Light and break the hold of reason, for within it

From the lowest dust to the highest heaven, all is joy.

Ḥikmat al-Ishrāq (Illuminationist Wisdom) and Ḥikmat-i Khosravānī (Ancient Persian Sapiential Philosophy) together form a distinctive current in Iranian philosophical and spiritual history, articulated most clearly by Shihāb al-Dīn Suhrawardī. Illuminationist Wisdom is grounded in the metaphysics of light, where existence itself is understood as varying degrees of luminosity, culminating in the Light of Lights. Knowledge, in this framework, is not attained solely through discursive reasoning but through inner unveiling and presence (ʿilm al-ḥuḍūrī). Reason remains valuable, yet it must be refined and ultimately surpassed by direct illumination, allowing the knower to participate in truth rather than merely describe it.

Khosravani Wisdom, by contrast, points to the ancient Persian tradition of sacred knowledge associated with just kingship, cosmic order, and the symbolic language of light and fire. Suhrawardī regarded this wisdom as a primordial philosophy transmitted through myth, symbolism, and ethical exemplars rather than systematic texts. Rooted in pre-Islamic Iranian spirituality, particularly Zoroastrian cosmology, Khosravani Wisdom emphasizes harmony between the moral, political, and cosmic realms. The “king” in this tradition is not merely a political ruler but a luminous soul whose inner order mirrors the order of the universe.

Suhrawardī’s genius lies in his synthesis of these two traditions, presenting Illuminationist Philosophy as a revival rather than an innovation. By integrating Khosravani Wisdom into an Islamic philosophical framework, he reconnected rational inquiry with spiritual insight and historical memory. This synthesis influenced later Persian thinkers, poets, and mystics, shaping a worldview in which light, ethics, and knowledge are inseparable. Together, Illuminationist and Khosravani Wisdom articulate a vision of philosophy as transformation—where true knowing is inseparable from becoming luminous in character and consciousness.

“Any form of wisdom that is founded upon the illumination and enlightenment of the intellect is called Illuminationist Wisdom.”

— Suhrawardī (Collected Works, Vol. 3, p. 32)

The feast is the intellect, not bread and broth;

The nourishment of the soul, O son, is the light of the intellect.

This statement by Suhrawardī and this verse from the Divān of Shams together express the central core of Illuminationist philosophy. Suhrawardī, by emphasizing the integration of reason and illumination, maintains that true knowledge is not attained solely through logical and rational thinking, but also requires an inner light and intuitive insight of the heart. In this school of thought, reason serves as the initial guide; however, a light beyond reason—emanating from the celestial realm—directs and completes the intellect.

This concept of illumination, particularly in its relationship to the enlightenment of reason, is also reflected in the Bahá’í Faith. In Bahá’í teachings, reason is regarded as a divine gift that distinguishes human beings from other creatures and serves as an instrument for the discovery of truth. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explains that reason is like a lamp that sheds light in the darkness of the material world; yet this same reason reaches its full perfection only when accompanied by the light of divine guidance. Thus, in the Bahá’í Faith as well, there is a strong emphasis on the integration of reason and divine light—that is, inner illumination.

Moreover, both Suhrawardī’s school and the Bahá’í Faith uphold a form of “spiritual enlightenment” that arises from rationality but is perfected through divine love and heavenly guidance. From the Bahá’í perspective, divine revelation is the light of guidance that shines upon the intellect, leading humanity toward the truth of existence, the unity of humankind, and the ultimate purpose of creation. This outlook resonates with Illuminationist philosophy, which understands knowledge not merely as logical data but as the illumination of heart and soul in the presence of truth.

From a comparative perspective, it may be said that both Suhrawardī’s Illuminationist philosophy and the Bahá’í worldview seek to elevate humanity from superficial and limited understanding to a deeper, more spiritual, and more luminous form of knowledge. Along this path, reason is likened to a mirror which, unless polished and receptive to divine light, cannot fully reflect reality. Thus, illumination in Suhrawardī’s wisdom and guidance in the Bahá’í Faith represent two expressions of a single truth: the illumination of the intellect through eternal guidance.

A profound link thus emerges between philosophy, mysticism, and the heritage of ancient Iran. Illuminationist Wisdom, as one of the major philosophical currents in Islamic civilization, was founded by Shihāb al-Dīn Suhrawardī as an effort to revive ancient Iranian wisdom, which he referred to as Khosravani Wisdom. This study examines the structure and foundations of Illuminationist philosophy and analyzes its relationship with Khosravani Wisdom and Iranian mysticism. Emphasis on light as the essence of being, the intuitive method of attaining truth, and the reinterpretation of pre-Islamic Iranian myths and wisdom are among the defining characteristics of this intellectual system.

In the history of Islamic philosophy, two major schools emerged: the Peripatetic tradition (based on Aristotelian rationalism) and the Illuminationist tradition (grounded in illumination and mystical intuition). Within this landscape, Suhrawardī’s Illuminationist Wisdom occupies a distinctive and exceptional position. It not only draws upon Greek rational philosophy but also, by returning to the roots of Iranian mysticism and ancient wisdom, represents a deliberate effort to indigenize philosophy within the Iranian–Islamic intellectual world.

The Shaykh of Illumination, in all of his works, sought to revive the divine wisdom of ancient Iran. Although Illuminationist Wisdom is the heir to two philosophical traditions—Greek and Iranian—drawing upon Pythagorean and Platonic schools in Greek philosophy and adopting the concepts of light and darkness from Iranian thought, it may be said overall that Suhrawardī integrated ancient Iranian wisdom into the broader trajectory of Islamic philosophy. Consequently, with the emergence of the Illuminationist tradition, philosophy and mysticism, reason and religion, became united.

Key Elements of Illuminationist Wisdom

Light and Darkness: Existence is defined according to degrees of light, ranging from pure Light to absolute darkness (matter).

Knowledge by Presence (ʿIlm al-Ḥuḍūrī): True knowledge is attained not through rational demonstration alone, but through direct, inward, and intuitive perception.

The Station of the Perfect Human Being: A person who attains illumination gains access to higher realms and becomes a conduit of divine grace.

The Integration of Philosophy and Mysticism: Suhrawardī unites Greek rational thought with the inward, esoteric dimensions of Islamic mysticism.

Khosravani Wisdom: A Reflection of Ancient Iranian Heritage

The term Khosravani Wisdom was employed by Suhrawardī to refer to the ancient wisdom of Iran that flourished during the era of spiritual and sage-kings such as Jamshīd, Kay Khusraw, and Zoroaster.

Suhrawardī believed that prior to the advent of Islam—and even before the Greeks—the Iranians possessed a distinctive illuminationist and luminous wisdom, preserved by Zoroaster and his successors. He regarded this wisdom as a form of inner knowledge acquired through spiritual discipline, purification of the self, and cleansing of the heart.

Characteristics of Khosravani Wisdom

A close relationship with Zoroastrianism and the religious teachings of ancient Iran.

Emphasis on light, purity, and the struggle against darkness, as reflected in the Gāthās of Zoroaster.

A mythic–mystical dimension expressed through symbolic narratives and archetypal figures.

A practical wisdom closely connected to ethical living and the conduct of kingship.

The Convergence of Illumination and Khosravani Wisdom: The Revival of Iranian Spirituality

Suhrawardī regarded himself not merely as a philosopher, but as a reviver of ancient Iranian wisdom. He believed that Greek Peripatetic philosophy, though valuable, lacked inner depth and spiritual vitality, and that only through its integration with Khosravani Wisdom could pure truth be attained.

In his view, the light of Zoroaster is the very same light sought by the Muslim mystic in the path of spiritual wayfaring. He maintained that true wisdom is universal, yet in its purest form it had been preserved by Iranian sages and therefore required reinterpretation and revival.

When the sun rises, every particle reveals itself;

Yet another light is needed for the hidden particles.

The Influence of Illuminationist Wisdom on Iranian Mysticism

Suhrawardī’s works exerted a profound influence on later Iranian mystics, including Rūmī, ʿAyn al-Quḍāt Hamadānī, Najm al-Dīn Rāzī, and even Ḥāfiẓ. In Rūmī’s Mathnawī, one can discern reflections of Suhrawardī’s luminous, intuitive, and mystical worldview.

Shams of Tabriz likewise speaks of light as the singular reality, and his emphasis on inward understanding and direct experience closely parallels the principles of Illuminationist Wisdom.

Even the veil of the sun is itself divine light;

Yet the bat and the night remain deprived of it.

Both remain behind distance and veils—

Either darkened in face, or left frozen and inert.

Rūmī was not a direct follower of Suhrawardī; however, in his use of the symbolism of light, he drew more from him than from any other thinker. Throughout his poetry, Rūmī repeatedly and extensively composed verses centered on light.

The radiance of the eternal Sun nurtured both soul and world;

Like a flower sweetened with sugar, it ripened and raised me.

The sacred soil of Iran is the cradle of three great religions. Great messengers such as Mithra, Zoroaster, and Bahá’u’lláh are regarded as the founders of these three spiritual traditions and of Khosravani Wisdom. The foundation and central symbol of all three is light. Mithra represents the sun as the source of light; Zoroaster venerates fire as the generator of light and energy; and Bahá’u’lláh embodies the Light of God. All three religions became international in scope. Mithra may be the earliest prophet portrayed as female; the surviving statues depict a woman crowned with rays of the sun. The French later created a monumental statue inspired by this image and presented it to the United States—the Statue of Liberty in New York.

O our noble Joseph, how gracefully you walk upon our roof!

O shatterer of our cup, O tearer of our snare!

O our light, O our feast, O our victorious fortune!

Stir our ferment, so that our grapes may become wine.

O our beloved and our aim, O our qiblah and object of worship!

You set fire to our incense—behold us in the rising smoke.

This light is the light of Bahá’u’lláh, which brings love into being.

My light has filled the world—look into my eyes;

They named me Bahá, though I am beyond all worth.

No one has tasted that morsel, not even a single particle taken;

Behold my dignity, for I taste that treasure.

Though the celestial sphere, the Throne, and the Footstool are far from creation,

Awake or asleep, at every moment I rise in ecstasy.

There, the world is all light—both angels and palaces;

Joy, celebration, and festivity abound—I bring back from there.

Gabriel stands as the keeper of the veil, the people of the inner realm behind it;

I am the jewel of their circle when I enter their ring.

Jesus stands beside Moses, Jonah beside Joseph;

Ahmad sits alone—meaning that I stand apart.

Love is the ocean of meaning, each a fish within the sea;

Ahmad is the pearl in the ocean—behold how I reveal it.

For a clearer understanding of Illuminationist Wisdom, two excerpts are presented below: one from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, and the other from the website Payām-e Andīsheh-Barangiz-e Asho Zartosht.

Ḥikmat al-Ishrāq (The Philosophy of Illumination)

Ḥikmat al-Ishrāq is the most important work of Shihāb al-Dīn Suhrawardī, in which he presented his theory of illumination at the end of the sixth and the beginning of the seventh Islamic centuries. Suhrawardī was the founder of a philosophical school that expanded and flourished after his death.

The book Ḥikmat al-Ishrāq by Shihāb al-Dīn Suhrawardī (549–587 AH) is among the most significant works encompassing experiential insight and Illuminationist philosophy. According to the author himself, Illuminationist philosophy is the wisdom of the Orient (ḥikmat al-mashāriqah), grounded in inner enlightenment and the claim of “supra-rational perception,” in contrast to Peripatetic philosophy, which is based on logical reasoning and analytical inference. Suhrawardī referred to the former as experiential wisdom (ḥikmat dhawqī) and the latter as discursive wisdom (ḥikmat baḥthī). He asserted that the origin of this wisdom lies in ancient Iran and that it later entered Greek philosophical circles—particularly those associated with Plato or the Alexandrian Platonists—through Iranian teachers or Greek students who had traveled to Iran.

This work is the first philosophical book written during the Islamic period that systematically addresses Illuminationist Wisdom. Several commentaries have been written on it, including that of Quṭb al-Dīn Kāzarūnī. Suhrawardī’s work consists of two main sections: logic and philosophy. In each section, he establishes and develops the principal discussions related to the Illuminationist system. In fact, Ḥikmat al-Ishrāq may be regarded as a concise synthesis of Suhrawardī’s entire body of knowledge and philosophical system.

The work has been published in the first and second volumes of al-Ḥikmah al-Ishrāqiyyah: the first volume contains the logical section, and the second presents the philosophical foundations of this seminal work of the Shaykh of Illumination. A comprehensive introduction to the book has been published in the Great Islamic Encyclopedia. The Persian translation of this work was carried out by Mas‘ūd Anṣārī, along with translations of two commentaries by Quṭb al-Dīn Kāzarūnī and Shams al-Dīn Shahrazūrī, as well as Mullā Ṣadrā’s marginal notes. These were published by Mowlā Publications in the Ḥikmat al-Ishrāq collection.

Suhrawardī’s philosophical theory held that existence is nothing but light, and that everything present in the universe—and everything that will come into being—is light. Some lights are subtle, others dense; some are composed of dispersed particles, while others consist of compacted ones.

End of quotation from Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia

Suhrawardī – The Shaykh of Illumination

A brief account of the Shaykh of Illumination (Farzāneh Forūgh)

Professor Henry Corbin (1903–1979), the eminent scholar of Sufism, comparative religion, and mysticism, writes in The Man of Light in Iranian Sufism:

“In northwestern Iran, Suhrawardī founded a great movement aimed at reviving divine wisdom and sacred knowledge—the ancient Zoroastrian Iran that predated Islam. By his death as a martyr in Aleppo, Syria, at the height of his youth, he sealed his success. He called his method of knowing God illumination (ishrāq), because its roots followed the Orient—not a geographical East, but an Eastern Light. Without doubt, the sages of ancient Iran were the foremost representatives and guardians of this wisdom. The philosophy and worldview whose adherents came to be known as the Illuminationists ultimately return, in their true meaning, to that Eastern origin—that is, pure Light.”

From Iranian culture, figures such as Asho Zoroaster, Farshushtar, Jāmāsp, Kay Khusraw, Fereydūn, and Bozorgmehr, as well as concepts such as the Amesha Spentas (especially Vohu Manah), the station of Khvarenah (Divine Glory), and the vision of the unity of being, are notable elements in the intellectual perspective presented by Farzāneh Forūgh.

Shihāb al-Dīn Yaḥyā ibn Ḥabash ibn Amīrak Abū’l-Fatḥ Suhrawardī, known as the Shaykh of Illumination and the Martyred Shaykh, was born in Suhraward near Zanjān in either 545, 550, or—according to Sayyid Ḥasan Naṣṣ, a noted Suhrawardī scholar—549 AH. He began his higher studies in Marāghah under Majd al-Dīn Jīlī (Gīlānī) and later continued his education in Isfahan under Ẓahīr al-Dīn Qārī. He endured great hardship in the pursuit of knowledge, philosophy, and ethical–mystical refinement, eventually becoming a preeminent philosopher and sage.

Suhrawardī chose Khosravani Wisdom—the philosophy of ancient Iran—as his intellectual path, a tradition founded upon Zoroaster’s vision of existence and the Divine. In search of companionship among seekers of divine love, mystics, and spiritual wayfarers, he traveled extensively; yet, according to his own writings, he never found a companion whose spiritual insight matched his own.

During one of his journeys to Syria, he arrived in Aleppo, where he met Malik al-Ẓāhir, the son of Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn Ayyūbī (the famous leader of the Crusades). Impressed by Suhrawardī’s wisdom, their meeting turned into friendship. Malik al-Ẓāhir invited him to remain there, and Suhrawardī accepted. Within a short time, he became the foremost authority among the philosophers and sages of the region. However, because he spoke his views openly and without fear, outwardly oriented scholars—attached to worldly rank and status—could not tolerate his extraordinary intellect and wisdom.

Eventually, under the pretext that his teachings endangered religion, they accused him of heresy and demanded his execution. Malik al-Ẓāhir initially refused, but they persisted and appealed to Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn Ayyūbī, who, for political reasons, ordered the execution of this sage. The sentence was carried out around 587 AH, when Suhrawardī was either 36 or 38 years old. Thus the world was deprived of a luminous and visionary intellect. Yet the pure rays of his divine-inspired thought endured across the ages, continuing to illuminate sound and uncorrupted thinking and to elevate human reason.

Dr. Gholām-Hossein Ebrāhīmī Dīnānī, the renowned philosopher and Suhrawardī scholar, writes in the introduction to The Ray of Thought and Intuition in Suhrawardī’s Philosophy:

“Suhrawardī did not seek to revive Khosravani Wisdom (the philosophy of ancient Iran) out of ethnic prejudice or racial bias. Rather, he was well aware that Western historians (such as Herodotus and others), out of arrogance and ethnocentrism, had ignored and concealed this wisdom. At the same time, certain extremist sects in the Islamic world emerged that ruthlessly sought to destroy the culture and civilization of ancient Iran, burning its scientific and philosophical works without restraint. Some Muslims believed that the Qur’an alone was sufficient for human guidance until the end of time, and that any book other than the sacred text should be burned. In his book al-Tanqīḥāt, Suhrawardī refers to the burning of many manuscripts and codices during the time of ʿUthmān.”

“As is well known, many books were burned by order of ʿUthmān, and for reasons of expediency the Companions did not oppose what took place. There can be no doubt that the justification for these burnings was deemed ‘expediency.’ Evidence exists that philosophical and sapiential works related to ancient Iran were destroyed. It is here that the task of figures such as Suhrawardī—and before him, the sage Abū’l-Qāsim Ferdowsī—became extraordinarily difficult. Yet neither of these deep-thinking and far-sighted figures feared the hardships of the path. Through tireless effort, they fulfilled their heavy historical responsibility. What is heard in Ferdowsī’s monumental work in epic language is expressed in Suhrawardī’s writings through philosophical reasoning and sapiential discourse, with equal power to illuminate pure hearts and unburdened minds.”

End excerpted from “The Status of Light and Fire in Zoroastrianism,”

by Mehrdād Qadrān, Payām-e Andīsheh-Barangiz-e Asho Zartosht.

We are all darkness, and God is Light;

From the Sun comes the radiance of this abode.

Within this house the light is mingled with shadow;

If you seek pure light, rise from this house to the roof.

Suhrawardī writes in Ḥikmat al-Ishrāq that:

“The lower light does not encompass the higher light, for the higher light always overpowers the lower light and shines upon it.”

Rūmī says:

The Light of Truth mounts the light of the senses;

Then the soul becomes inclined toward the Truth.

What does a riderless steed know of the way?

A king is needed to recognize the royal road.

Turn toward the senses whose light has a rider,

For that light is well-governed by the Light.

The Light of Truth adorns the light of the senses—

This is the meaning of Light upon Light.

Sensory light draws one toward the Pleiades;

The Light of Truth carries one toward the Most High.

The higher Light causes love to be kindled within the lower light.

By the God who has existed from eternity—

Living, Knowing, Powerful, and Self-Sustaining.

His light lit the candles of love,

Until a hundred thousand secrets were made manifest.

From a single decree of His, the world was filled

With lover and love, ruler and ruled.

Your desire is copper, and the elixir is the light of love;

By the light of love, the copper of your being is turned to gold.

It is from jealousy of that light that perfected reason

Is made blind and deaf by the intensity of its beauty.

Rūmī says that the Light of Truth has many different veils.

For the Light of Truth has seven hundred veils—

Know that the veils of light are layered upon layers.

Behind each veil a people have their station;

These veils stand in ranks, row upon row, up to the Imam.

Those in the furthest rank, because of their weakness,

Their eyes cannot endure any greater light.

And the rank before them, though stronger in sight,

Still cannot bear a brighter radiance.

That brightness which is the first life itself

Is torment to the soul and trial for the cross-eyed.

Yet this double vision lessens little by little,

Until, passing beyond the seven hundred, one becomes the sea.

The fire that refines iron or gold—

How could it befit water or a tender apple?

Apple and water possess a subtle rawness;

They do not require the delicate endurance of iron.

But iron is refined by those subtle flames,

For it is drawn toward the blaze of that dragon-like fire.

That iron is poor, yet steadfast in suffering—

Under hammer and flame it glows, red and radiant.

The Shaykh of Illumination believes that “joy has an affinity with light,” and Rūmī says:

The day Your light shines through my window,

I dance with joy in the house like a mote of dust.

According to Suhrawardī, since God is the Light of Lights and His light is not directly visible to our eyes, when it reaches the world of existence it chooses a star such as the sun and manifests itself through it. Each object and being in this world benefits from this manifestation according to its own capacity. Just as God, in the spiritual realm, is the Light of all lights, so too the sun, in the material realm, is the light of all lights. This does not mean worship of the sun; rather, honoring and revering the sun is incumbent upon all.

Some examples of the role of light and the sun in the poetry of Rūmī:

How warm we are, how warm we are with this love, like the sun—

How hidden, how hidden, and yet how manifest You are, O God!

When the sun revealed its face,

All were made to bow like shadows.

Come, for the light of the heavens has adorned the earth;

The blossom is the light of Truth, and the tree is like a niche of light.

You are but a shadow—be annihilated in the sun’s radiance;

How long will you look at your own shadow? See His light as well.

Illuminationist Wisdom and Khosravani Wisdom, drawing upon reason, intuition, and the spiritual traditions of ancient Iran, created a unique philosophical and mystical system that remains alive within Iran’s intellectual heritage. By rediscovering Khosravani Wisdom, Suhrawardī demonstrated that Iranian thought could not only stand alongside Greek philosophy, but also elevate it. Even today, revisiting this wisdom can inspire a form of spiritual, indigenous, and human-centered thinking—one that honors both the intellect and the heart.

All three Iranian prophets—Mithra, Zoroaster, and Bahá’u’lláh—together with mystics and Khosravani sages such as Suhrawardī, Rūmī, ʿAṭṭār, Ferdowsī, Sanā’ī, Ḥāfiẓ, and others, played a profound role in shaping and transmitting this wisdom.

Illuminationist Wisdom from Hegel’s Perspective

Hegel’s works are extensive and often complex; however, there is a relevant passage from his Lectures on the Philosophy of History in which he discusses spirituality and the symbolic significance of light in the context of Persian civilization:

“The principle of the Persian religion is light; and light, taken abstractly and in itself, is the source and essence of all life and movement. The sun is the embodiment of light, and therefore the image of the sun is the point upon which Persian worship is chiefly centered.”

This quotation reflects Hegel’s interpretation of Persian religious beliefs, particularly Zoroastrianism, in which light symbolizes purity, knowledge, and the divine. Through this lens, Hegel presents his view of how the Persians contributed to humanity’s spiritual development by advancing the idea of monotheism and an abstract conception of God represented through light. According to Hegel, this concept played a vital role in the dialectical process of the unfolding of the World Spirit and represents a significant evolution beyond the nature-centered and pantheistic worldviews of earlier civilizations.

The Future of Ancient Persian Sapiential Philosophy

In the Name of the Merciful God

O Pure Lord, from the beginning You made the soil of Iran fragrant like musk—stirring, knowledge-bearing, and gem-scattering. From its east, Your sun has ever shone forth, and in its west Your radiant moon has appeared. Its land is love-nurturing; its plains are like a restful paradise, filled with life-giving flowers and plants; its mountains abound in fresh, tender fruits; and its meadows rival the gardens of heaven. Its consciousness was the message of the Divine Messenger, and its vitality like a deep, surging sea.

There came a time when the fire of its knowledge was extinguished, and the star of its nobility lay hidden beneath a veil. Its spring turned to autumn; its charming flower garden became a field of thorns; its sweet springs turned brackish; and its beloved great ones became wanderers, scattered from land to land. Its radiance grew dim, and its rivers ran thin—until the ocean of Your bounty surged forth and the sun of Your generosity rose again. A new spring arrived; a life-giving breeze blew; beneficent clouds poured rain; and the rays of that nurturing Sun shone forth. The land was stirred; the dust-heap became a rose garden; the black earth turned into the envy of orchards. The world became a new world, its renown grew exalted; plains and mountains turned green and flourishing; and the birds of the meadow became companions in song and melody.

This is the hour of joy; it is a heavenly message; it is an eternal moment. Awake, awake, O Most Gracious Lord! Now an assembly has been formed and a group has become united in purpose, striving with all their hearts to benefit from the rain of Your bounty, to nurture young children in the embrace of awareness through the power of Your education, to make them the envy of the learned, to teach them the heavenly teachings, and to manifest divine generosity. Therefore, O Merciful Lord, be their support and refuge; bestow strength upon their arms, that they may attain their aspirations, rise above limitation and excess, and make that land a likeness of the world above.

— (Provisional translation) From the Prayers and Meditations of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Vol. 1

National Bahá’í Publishing Trust – Iran, p. 80

After the Muslim Arab invasion of Iran in the seventh century CE (following the Battle of Nahāvand in 642 CE), the Sasanian political structure collapsed, and Iran became part of the Islamic Caliphate. This profound political transformation dissolved or weakened many of Iran’s governing, bureaucratic, and military institutions. Subsequent caliphal dynasties—particularly the Umayyads—adopted policies that weakened the indigenous Iranian language and culture, including changing the official administrative language to Arabic. During this period, many written and linguistic works from earlier eras were either lost or pushed to the margins.

With the Islamization of governmental and religious structures, Arabic replaced Middle Persian (Pahlavi) in official, scholarly, and religious domains. Many documents and scientific and religious texts were written in Arabic, and new generations of Iranians turned to Arabic for religious education and Islamic sciences. As a result, Middle Persian—which carried a large portion of Zoroastrian culture, myths, and ancient customs—gradually fell into obscurity. Nevertheless, in the third century AH, cultural movements such as the Shuʿūbiyya and great poets like Rudaki and Ferdowsi played a crucial role in reviving the Persian language in the form of New Persian (Dari).

Despite these pressures, Iranian culture did not disappear; rather, in many cases it adapted to new circumstances and even absorbed Islamic-Arab elements. New Persian (Dari), enriched with Arabic vocabulary, gave rise to a fresh and powerful language that became the medium for some of the greatest literary, mystical, and philosophical works of the post-Islamic era. Iran’s rich literature—embodied in works such as the Shāhnāmeh, Golestān, Mathnavi-ye Maʿnavi, and many others—demonstrates the survival of the Iranian spirit in a new form. Thus, although the Arab invasions led to the loss of parts of pre-Islamic culture, Iranian Khosrowani culture continued its path of survival and flourishing through wisdom, creativity, and adaptability.

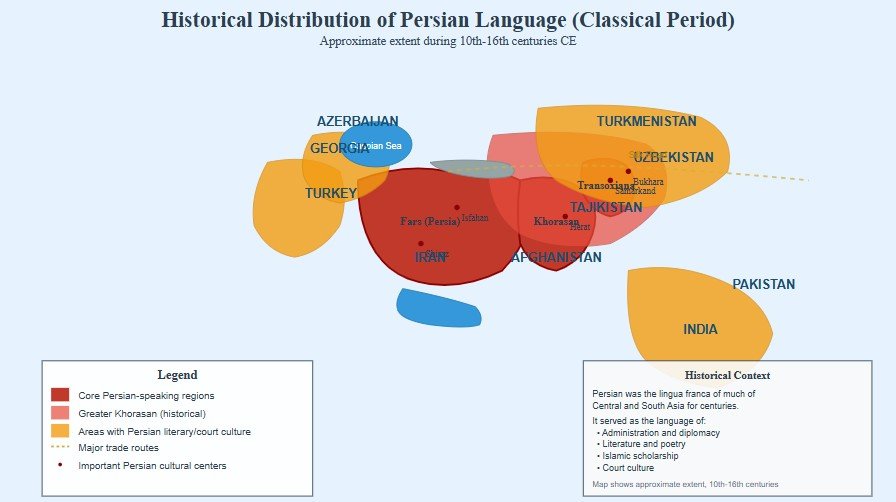

Main Persian-speaking regions and Khosrowani culture:

Iran – still the principal Persian-speaking country

Afghanistan – where Dari Persian is an official language

Tajikistan – where Tajiki (a Persian dialect) is the official language

Other regions with historical influence:

Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan – parts of historical Greater Khorasan

Turkey – parts of the Ottoman Empire where Persian was used at court

Georgia and Azerbaijan – Caucasian regions influenced by Persian culture

India and Pakistan – where Persian was the language of the Mughal court

Greater Khorasan

Greater Khorasan, historically recognized as one of the most important regions of the medieval Islamic world, encompassed a vast territory stretching from northeastern present-day Iran to southern Turkmenistan, northern Afghanistan, and parts of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. The name derives from the Middle Persian word Khwarāsān, meaning “the land of the rising sun,” reflecting its position in the eastern reaches of the Persian Empire. Under the Sasanian Empire (224–651 CE), Khorasan functioned as a vital frontier province, defending against Central Asian nomadic incursions while facilitating trade along the Silk Road. Its strategic importance was heightened by its role as a gateway between Persia, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.

The Islamic conquest of Khorasan in the seventh century marked a transformative period in the region’s history. Arab armies led by commanders such as Qutayba ibn Muslim gradually defeated local Sasanian rulers and established Islamic governance around 705 CE. However, the process of Islamization was gradual, and many Persian administrative practices and cultural traditions persisted under Arab rule. During the Umayyad period, Khorasan became especially significant as a launching point for further conquests into Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. The blending of Arab, Persian, and local cultures created a unique synthesis that profoundly influenced Islamic civilization.

Khorasan reached its political zenith during the Abbasid Revolution (747–750 CE), when Abu Muslim al-Khorasani led a successful uprising from the region that ultimately overthrew the Umayyad Caliphate. The Abbasids, who came to power with crucial Khorasani support, established their new capital in Baghdad while maintaining strong ties to their eastern base. Subsequently, Khorasan became the heartland of several semi-independent dynasties, including the Tahirids (821–873), Saffarids (861–1003), and most notably the Ghaznavids (977–1186) and Ghurids (1011–1215). These dynasties not only preserved the region’s political autonomy but also patronized Persian literature, art, and scholarship, contributing to what many regard as a Persian cultural renaissance.

The Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century devastated Greater Khorasan. Cities such as Merv, Balkh, and Herat suffered massive destruction and population loss. Although the region never fully regained its former splendor, it remained culturally and economically significant under later rulers, including the Ilkhanids, Timurids, and later the Safavid, Mughal, and Ottoman empires. Modern borders drawn in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries divided historical Khorasan among several nation-states, yet its legacy endures in the shared cultural and linguistic heritage of Persian-speaking peoples across Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. Today, the memory of Greater Khorasan continues to shape regional identity and cultural expression throughout this historically interconnected area.

Historical and cultural role

Many believe that New Persian (Dari) was nurtured in Khorasan and from there spread to other parts of Iran and beyond. As a scientific and literary center, Khorasan was the cradle of many great Iranian scholars, poets, thinkers, and mystics, including:

Abu Rayhan al-Biruni

Avicenna (Ibn Sina)

Ferdowsi of Tus

Naser-e Khosrow Qobadiyani

Attar of Nishapur

Omar Khayyam of Nishapur

Jalal al-Din Rumi

Bayazid Bastami

Abu Saʿid Abu’l-Khayr

Abdullah Ansari

Cultural and linguistic preservation through poetry

Iranian poetry—especially classical works—has long served as a living treasury of the Persian language across centuries. Poets such as Ferdowsi, Hafez, Saʿdi, Rumi, and Khayyam stabilized grammatical rules, vocabulary, idioms, and literary devices through their refined and rich use of Persian.

Ferdowsi’s Shāhnāmeh is a prime example. Written around the year 1000 CE, this epic—using pure Persian with minimal Arabic influence—played a decisive role in preserving Iranian identity and the Persian language after the Arab conquest. The Shāhnāmeh is often regarded as a central pillar of Persian linguistic survival.

Persian poetry, through its specific forms such as the ghazal, quatrain, and masnavi, contributed to the standardization of the language in terms of structure and aesthetics. Meter and rhyme demanded careful word choice and grammatical precision. The teaching and memorization of poetry strengthened the standard language across generations and regions.

Persian poetry has consistently functioned as an instrument of cultural resistance—whether against Arabization in the early Islamic period, against Westernization in the modern era, or against globalization today. Classical poets, by emphasizing Iranian identity, bestowed dignity and pride upon the Persian language. In modern times, poets such as Nima Yushij and Forough Farrokhzad renewed the language while preserving its Persian essence.

Poetry and prose have always been central to Iran’s oral tradition—recited in homes, schools, gatherings, and public spaces, and transmitted from generation to generation. Children become familiar with vocabulary and rhythmic language from an early age through memorization and recitation. By encompassing ethical, philosophical, mystical, and patriotic themes, poetry has anchored the Persian language in the collective memory of Iranians.

Persian poetry and prose have also provided a fertile ground for linguistic creativity, introducing innovations in metaphor, symbolism, and grammatical structures. Poets such as Rumi, Hafez, and Khayyam expanded the mystical and symbolic lexicon, while modern poets introduced new syntactic and semantic forms—without erasing Persian linguistic identity.

All the parrots of India are made sugar-breaking

By this Persian candy that goes to Bengal.

— Hafez

Persian poetry and prose have played a vital role in spreading and preserving the Persian language beyond Iran’s borders, including Afghanistan, Tajikistan, India, and Central Asia.

Persian poetry and prose are not merely literature; they constitute one of the principal pillars of the Khosrowani cultural language. Through their beauty, coherence, and cultural depth, they preserved, enriched, and transmitted this language through time—up to the era of Bahá’u’lláh—so that future generations might draw upon this beauty in their own writings.