Samāʿ is the gentle solace of living souls;

who knows that it is the very soul of the soul?

Samāʿ, in its literal sense, means hearing, audition, or a pleasing sound. In Sufi terminology, samāʿ refers to a state of spiritual rapture and illumination—an involuntary separation from the self and a moment of annihilation—over which the mystic has no conscious control. The Sufis say that samāʿ creates a condition in the heart and soul called wajd (ecstasy). This ecstasy gives rise to certain bodily movements: if the movements are unmeasured or irregular, they are called iḍṭirāb (agitation); if they are measured and harmonious, they take the form of clapping and dance.

“O friends of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and servants of the Beauty of Abhá! Blessed, blessed are you, for you have drunk this overflowing cup from the hand of the Cupbearer of mysteries, and have become so intoxicated that, dancing in this arena, you have clasped the gracious Beloved to your hearts. That is, you have attained unto divine knowledge and have been drawn by His love. You have opened your tongues in praise and glorification, and with heart and soul have striven in the path of God. This is a mighty bestowal and a grace without equal or peer.”

Provisional translation

Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Volume 6

Dance there, where you shatter the self,

where you tear out the cotton from the root of desire.

They dance and charge upon the field;

the brave dance within their own blood.

When they are freed from the grip of self, they clap their hands;

when they leap beyond imperfection, they break into dance.

Their musicians beat the drum from within,

and seas, in their ecstasy, clap their waves.

You do not see it—but for their ears,

even the leaves upon the branches are clapping.

You do not see the leaves clapping their hands;

it is the ear of the heart that is needed, not the ear of the body.

Close the ear of the head to jest and falsehood,

so that you may behold the radiant city of the soul.

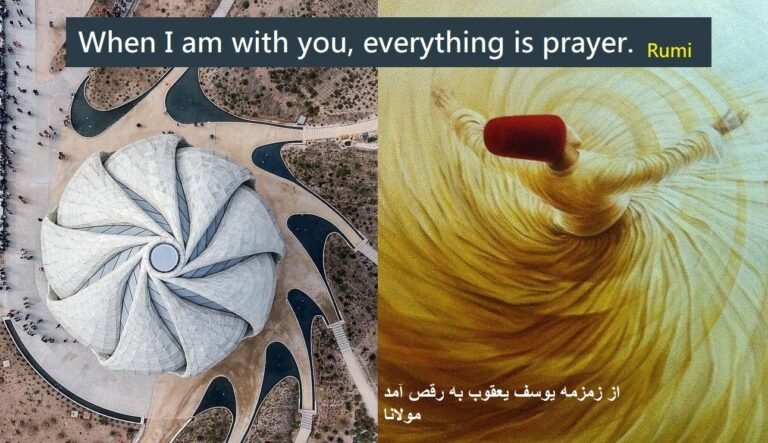

In the ritual dance of samāʿ, the position of the hands is such that one is raised toward the sky while the other is directed toward the earth. This posture signifies that the dancers serve as intermediaries—receiving divine grace from heaven and conveying it to the earth. The turning of the dancers changes gently: one hand toward the sky, one toward the earth, while they slightly incline their necks as a sign of acknowledgment of human limitation and fault, and they continue to turn. This movement symbolizes that we are merely intermediaries, and that God alone takes whatever He wills from heaven and brings it down to the earth.

As the turning continues, the dervishes’ arms open wider, they face toward God, and their necks incline further. Yet despite this, they maintain their balance and continue to whirl. In many cases, maintaining balance becomes more difficult when the eyes are closed. This dance must be witnessed up close to more fully grasp and feel its beauty and mystical quality.

“Music and song are among the essential pillars of Sufi spirituality, especially in the mysticism of Shams. Music, in his view, is the only means capable of removing the veil between human beings and God. Indeed, this dance and samāʿ connect the seeker to God.”

—ʿAbdolhossein Zarrinkoub, Step by Step to the Meeting with God, p. 156

During the dance, the Sufi listens to both the earth and the heavens, so as to hear the divine mysteries and not be deprived of the new manifestations of the Divine.

My ear has grown weary from waiting for that—

that from some side a sweet sound might suddenly arrive.

The ear has become attuned, an ear for drinking melody—

one that hears the joyful samāʿ from both earth and heaven.

The samāʿ of this earth is but a branch of the samāʿ of the heavens;

and the samāʿ of the body is a branch of the samāʿ of intellect and soul.

The Dance of Samāʿ for the Manifestation of the Divine Messengers

The spring of souls has come—O tender branch, arise and dance!

When Joseph enters in, Egypt and sugar burst into dance.

The blind and the deaf of the world beheld healing from the Messiah;

Jesus son of Mary proclaimed: “O blind and deaf—come, dance!”

The Following Material Is Adapted from the Website Kajavar,

written by Parisa Homayouni

An Introduction to Samāʿ

In recent decades, one occasionally encounters articles in American newspapers about the teaching of “Sufi dance,” and “Sufi dance” has even become a common method for self-cultivation. Yet, dance in Islam has traditionally been regarded as reprehensible, because throughout the history of religions, dance has generally been associated with ecstasy and spiritual states that remove a person from their ordinary condition, drawing them into rotation around a particular axis.

Undoubtedly, during the medieval Islamic period, the banquets of affluent Muslims often concluded with music and dance.

However, within a religious framework, dance—which is essentially a phenomenon of music and melodic sound—comes into tension with Islam’s law-centered character, since it may divert a person from the path ordained by God. For this reason, some opposed dance outright. Over several centuries, numerous articles and treatises were written against dance due to its alleged satanic influences.

Yet in the ritual of samāʿ, within that state of whirling and complete surrender, there exists a hidden fervor that brings both the dancer and the observer into ecstasy. Samāʿ is the outward expression of Rumi’s inner thought. He chose poetry, music, and dance as means to describe what is essentially indescribable. It has been reported that Rumi would dance with his companions in streets and marketplaces, and it is said that even the funeral procession of Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn Zarkūb was carried to the cemetery with dance and drum at Rumi’s indication.

The History of the Samāʿ Ceremony

There is no precise information regarding the history of samāʿ prior to Islam. What is certain, however, is that samāʿ and sacred dance offered to God have roots in ancient mythological traditions. In verses of the Torah, reference is made to the samāʿ of the Prophet David, who “leapt and danced before the Lord.” Likewise, in the Gospel, reference is made to the dance and samāʿ of Mary upon the steps of the altar.

After the advent of Islam and until the year 245 AH, no trace of samāʿ appears in Muslim ritual practice. In that year, Dhū’l-Nūn al-Miṣrī permitted his disciples to hold the first gathering of devotional singing and samāʿ. Shortly thereafter, in 253 AH, the first formal samāʿ circle was established in Baghdad by ʿAlī al-Tannūkhī.

Although it is not entirely clear when samāʿ gatherings formally began, we know that samāʿ had a non-Islamic religious background and was practiced in ancient times in places of worship. In early Islam, samāʿ as practiced in Sufi gatherings did not exist. In 245 AH, Sufis in the Great Mosque of Baghdad received permission from Dhū’l-Nūn al-Miṣrī to perform samāʿ, and in 253 AH the first samāʿ circle was formally organized by ʿAlī al-Tannūkhī, a companion of Sarī al-Saqaṭī.

The Samāʿ Ceremony Today

Today, samāʿ ceremonies are held magnificently in cities such as Konya, Cairo, and Aleppo. The ceremony begins with praise of the Prophet Muhammad and concludes with prayer. It includes music, dance, whirling, and symbolic movements, which are described below.

The Space of the Ceremony

The circular space in which the dervishes whirl symbolizes perfection and unity. It has no beginning or end and therefore represents time itself. The circle is also a symbol of God; an ancient text states that God is like a circle whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere. The circle is the simplest curve and, in truth, a polygon with infinitely many sides—a union of simplicity and infinity. Because it has neither beginning nor end, it signifies eternity.

Musical Instruments Used in Samāʿ

A section of the samāʿ hall is devoted to the display of musical instruments, which include:

ney (reed flute), rabāb, daf (frame drum), tanbur, kamancheh, kaman, and tar.

Ney

The ney symbolizes harmony in nature and represents the soul that has been separated from its true homeland. With its penetrating, sorrowful sound, it laments to God and yearns to return to the reed-bed from which it was cut.

Daf

The rhythmic beat of the daf in samāʿ symbolizes the divine command “Be!” issued by God at the creation of the universe. Following this command, the sound of the ney represents the sacred breath which, after the descent of divine light, breathed life into lifeless bodies:

“His command, when He wills a thing, is only to say to it: ‘Be!’ and it is.”

After the sound of the ney, the shaykh and all the dervishes—symbolizing bodies that have received life through this sacred breath—touch the ground with their hands. This act signifies their will to become the Perfect Human Being and the fulfillment of the command “Be” by those who have entered the path of discovering truth.

Dance in Samāʿ

Dance in samāʿ is symbolic. Before the physical body dies, the dervish causes the ego to die. He opens his arms and begins to whirl. During samāʿ, the right hand is raised upward, as if in prayer, and the left hand is turned downward. The dervishes are intermediaries between God and humanity, between heaven and earth: they receive from God and bestow upon humankind, keeping nothing for themselves.

In samāʿ, the dervish keeps the left foot firmly planted on the ground and rotates around it with the right foot. With each turn, and in silence, he repeats the remembrance of God. Without colliding with others and without disturbing harmony, he continues to whirl—like the planets of the solar system revolving around the sun.

Salām (The Four Greetings)

The samāʿ ceremony consists of four salāms, representing the four stages of the spiritual path: Shariah, Tariqah, Haqiqah, and Maʿrifah. At the end of each salām, the dervishes form groups of two, three, or four and bow toward the central point—symbolizing Rumi—leaning upon one another. This division symbolizes unity and solidarity.

During the first three salāms, the dervishes whirl both around themselves and around the space. In the fourth salām, they remain in place and whirl only around the shaykh.

At one point in the ceremony, a verse is recited with the following meaning:

“To God belong the East and the West; wherever you turn, there is the Face of God. Surely God is All-Encompassing, All-Knowing.”

The samāʿ concludes with prayer, and all dervishes and musicians follow the shaykh, bow before the ceremonial space, and then depart.

End of article by Parisa Homayouni.

The Following Material Is from Donyā-ye Eqtesād Newspaper

Issue No. 6064, Saturday, Mordad 6, 1403

“The Mystery of Samāʿ” — Interview with Konya’s Senior Samāʿ Performer, Hossein Naqavi al-Hosseini

Question: During samāʿ, many movements are performed. What do they signify?

Answer:

Mawlana connected us to the Shariah of Islam. In samāʿ, the left foot is placed firmly and resolutely on the ground—this comes from our Shariah—while the right foot turns 360 degrees, symbolizing the journey through the seventy-two nations. Every movement, including the opening of the arms, has a specific meaning. Initially, the left foot does not move, and the left hand rests on the right shoulder while the right hand rests on the left shoulder—this signifies divine unity (tawḥīd).

When the right hand opens and the left remains closed, it signifies lā (“no”). The open right hand conveys the grace received from God to others. The garments also have symbolic meaning: the black outer cloak represents earth. Removing it symbolizes entering samāʿ, while the white garment beneath represents the shroud of the ego. After the samāʿ ends, the performer returns to his original form.

Question: What is the significance of the red sheepskin?

Answer:

The master of the samāʿ sits upon the red skin, symbolizing the path Mawlana took toward Truth. The red color signifies sunset—the moment Mawlana turned away from the world and toward the Hereafter. The one seated upon it is called the post-neshin (the one who sits upon the post).

Question: What can you tell us about Sufism and etiquette in samāʿ?

Answer:

While performing samāʿ, proper conduct is essential. Sufism begins with etiquette; thus, manners are central in the Mevlevi path. In tekkes, we frequently encounter those who say “yā Hū”, and from all our brothers we expect a Sufi life filled with courtesy, ethics, and humility.

End of quotation.

Opening the arms signifies that the mystic longs to reach the Beloved and to embrace Him.

When love throws its arms around my neck, what can I do?

I draw it close and hold it tight, even in the midst of samāʿ.

When a particle’s embrace is filled with the radiance of the sun,

all things break into dance, in samāʿ beyond all outcry.

The Manifestations of divine revelation shine like the world-illuminating sun, casting their light upon the entire world.

A sun—not from the East, nor from the West—

shone forth from the soul;

from its light, like particles,

our walls and doors burst into dance.

We are but particles, drawn after that sun;

our way of being, day and night,

is the dance of the mote.

When the sun rises, every particle reveals itself;

a different light is needed

for the hidden particles.

In the radiance of His sun, why should I not dance?

When the particle begins to dance,

it remembers its source—Me.

Every particle became pregnant

from the shining of His face;

from that delight,

each particle gives birth to a hundred more.

Look at the mortar of the body—

how, from love, the soul grows light;

until the particle pounds and grinds itself,

becoming nothing but itself.

Through the stamping of the feet in the dance of samāʿ, the Sufi places beneath his feet all that is other than Him; this signifies trampling down and crushing the desires of the ego.

When you enter samāʿ, you step beyond both worlds;

this world of samāʿ lies beyond the two worlds.

Though the roof of the seventh heaven is lofty indeed,

the ladder of samāʿ has passed beyond that roof.

Trample beneath your feet all that is other than Him—

samāʿ belongs to you, and you belong to samāʿ.

In the Holy Qur’an, God has promised to give the believers a sealed, pure wine to drink, and the one who performs samāʿ drinks from this wine:

“They will be given to drink of a sealed, pure wine.”

(Qur’an 83:25)

Today there is samāʿ—unceasing and ever-flowing—and a cupbearer;

the bestowed goblets are passing around among the gathering.

The command of “God is the Cupbearer” has arrived—drink!

O body, become wholly soul, not merely a companion of purity.

O cycle, what a cycle you are! O day, what a day!

O garden of good fortune, how full of leaves and song you are!

From dust, in this age, people rise again—

for this is the blast of the Trumpet, sounding its call.

Whirling around oneself signifies the presence of the Lord in every direction of life—that wherever one turns, God is there. As stated in the Holy Qur’an:

“To God belong the East and the West; wherever you turn, there is the Face of God. Truly, God is All-Encompassing, All-Knowing.”

(Qur’an 2:115)

Wherever I lay my head, it is a place of prostration to Him;

in the six directions—and beyond the six—He alone is the object of worship.

The garden, the flower, the nightingale, and the samāʿ, and the Beloved—

all of these are but pretexts; He alone is the true purpose.

True Samāʿ gives rise to true love.

Love is not that you rise up at every moment

and set yourself spinning beneath your own feet.

Love is this: when you enter samāʿ,

you stake your soul and rise beyond the two worlds.

In samāʿ, the dervishes symbolically envision their Master as the sun,

and, like planets revolving around the sun, they begin to whirl.