I traveled to every city and ran through them all,

Yet I found no city like the city of Love.

Konya is a historic city in central Turkey (Anatolia), best known as the home of Jalāl ad-Dīn Rumi (Mawlānā) and the cradle of Sufism’s Mevlevi (Whirling Dervish) order.

Why Konya matters

Spiritual center: Rumi spent his final years here; the Mevlana Museum (his mausoleum) is a major pilgrimage site.

Seljuk legacy: Konya was the capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum (11th–13th c.), reflected in its mosques, madrasas, and tilework.

Living tradition: The Sema ceremony (whirling) continues as a ritual of remembrance and devotion.

The city of Konya, during the time of Mawlānā Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Balkhī (Rumi), was one of the most important scientific, cultural, and spiritual centers of the Islamic world. Located in the heart of Anatolia, the city experienced its political and spiritual flourishing in the 7th century AH / 13th century CE. Below is a closer look at the condition of Konya during Rumi’s lifetime:

1. Konya: Capital of the Seljuks of Rum

During Rumi’s time, Konya was the capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. This dynasty, a branch of the Great Seljuks, ruled Anatolia from the 5th to the 7th century AH. Under rulers such as Kayqubad I and Kaykhusraw II, Konya experienced remarkable prosperity. By supporting scholars, poets, jurists, and Sufis, these rulers transformed Konya into a major cultural and religious hub.

2. A Center of Learning and Mysticism

Konya was one of the leading centers of religious sciences, philosophy, and mysticism. Madrasas, mosques, khānaqāhs, and lodges flourished throughout the city. After migrating from Balkh and traveling through Nishapur, Baghdad, Mecca, Damascus, and finally Anatolia, Rumi settled in Konya and taught at the Alaeddin Madrasa. The city became a meeting place for many great scholars and mystics of the era and, due to its spirit of openness, attracted numerous seekers of knowledge and Sufism.

3. Cultural and Ethnic Diversity

Konya at that time was a multicultural and multiethnic city. Turks, Persians, Greeks, Armenians, and Christians lived side by side. This diversity created an environment conducive to interfaith dialogue and intellectual exchange. In such a setting, Rumi articulated universal concepts such as love, unity, and divine knowledge, transcending ethnic and religious boundaries.

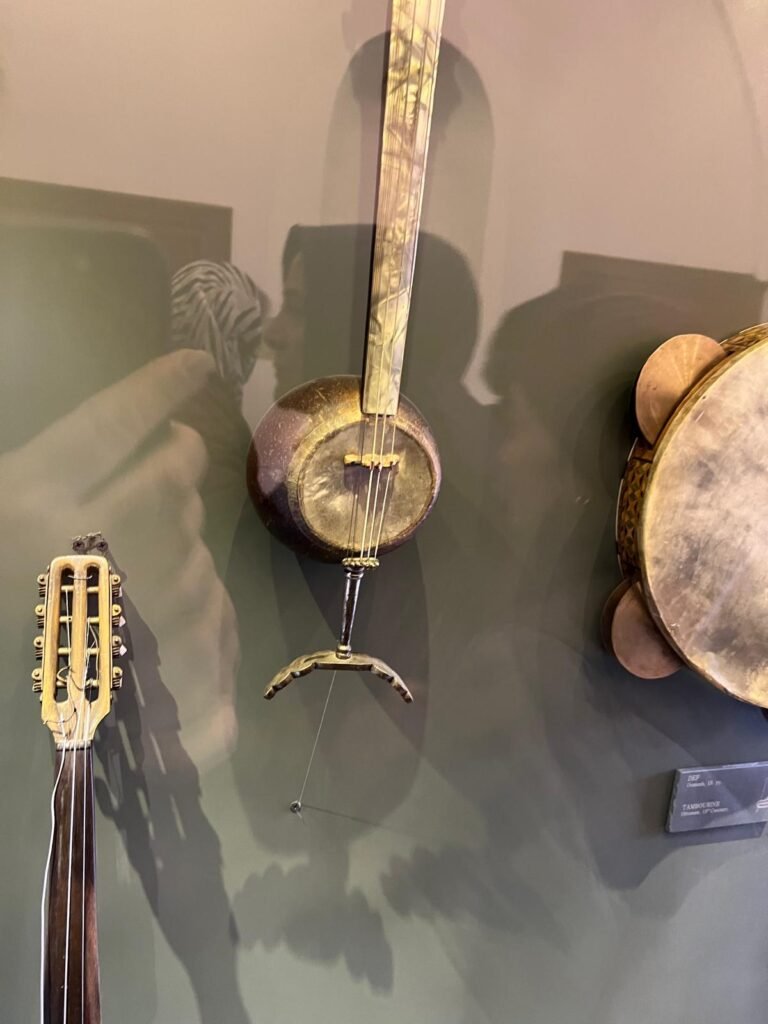

4. Konya as a Center of Sufism and the Sama Ceremony

Following Rumi’s spiritual transformation and his meeting with Shams of Tabriz, Konya became a major center for the development of the Sama ritual and the Mevlevi mystical path. Sama gatherings, recitations of the Mathnavi, and mystical poetry were held in Sufi lodges. After Rumi’s passing, his tomb in Konya became an important pilgrimage site, and the Mevlevi Order took shape in that very city.

5. Political Support for Rumi

The Seljuk sultans—especially Kayqubad—and local rulers such as Parvaneh supported Rumi and honored his gatherings. This patronage allowed Rumi to teach disciples freely, compose the Mathnavi, and spread mystical teachings without political pressure.

6. Social and Economic Conditions

Although Konya was relatively prosperous, like other Islamic regions it was not immune to Mongol invasions and regional unrest. Nevertheless, the presence of scholars and Sufis provided the people with a sense of spiritual stability.

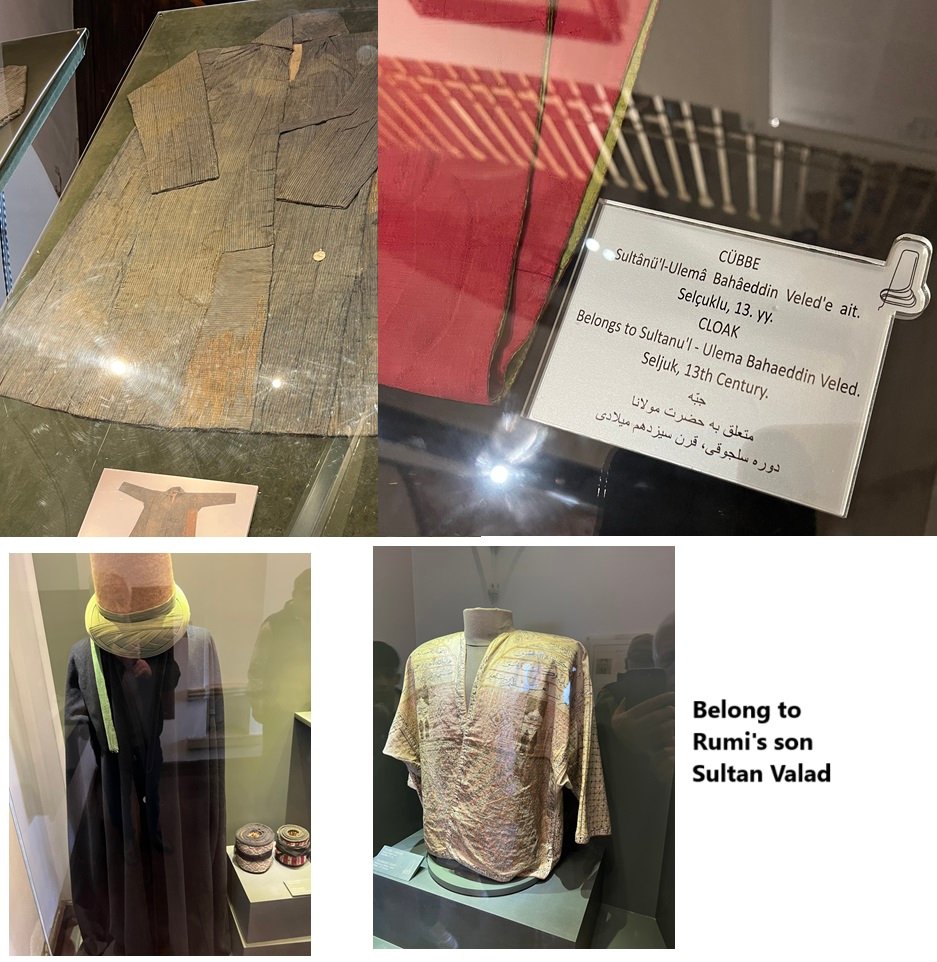

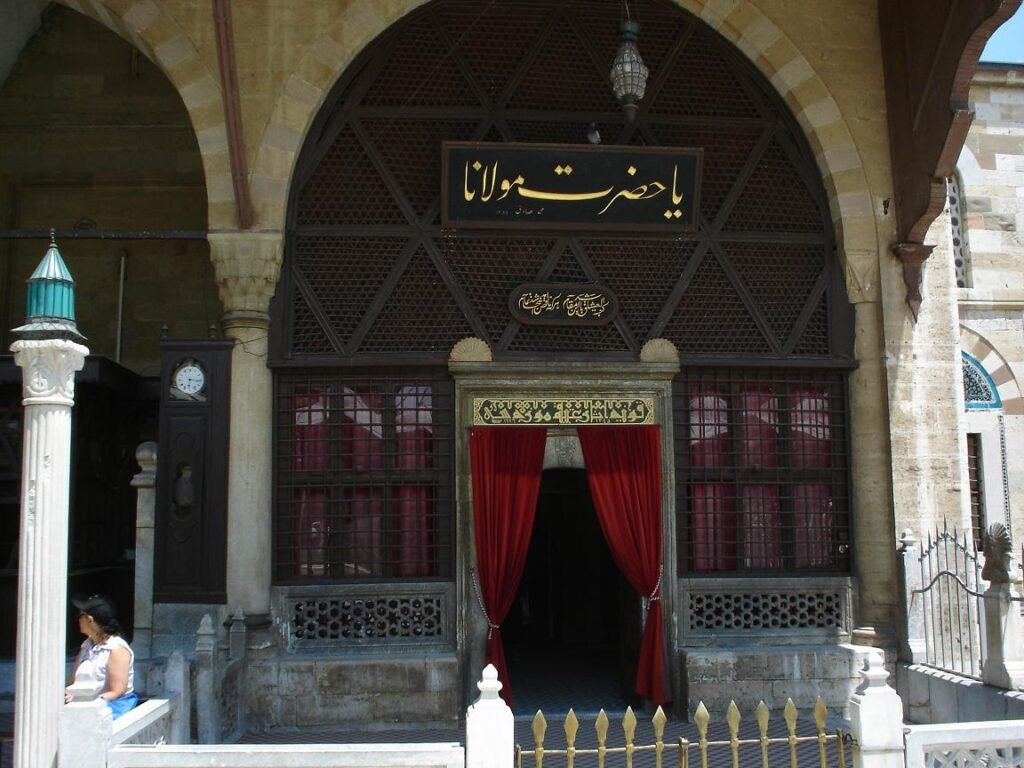

History of Rumi’s Mausoleum

The history of Rumi’s mausoleum dates back to the time when Rumi moved to Konya at the invitation of the Seljuk ruler Sultan Alaeddin Kayqubad. Rumi inherited his father’s rose garden, known as “Erm Baghcheh,” where his father was buried. After Rumi’s death, he was also laid to rest beside his father.

The mausoleum dates to 673 AH / 1274 CE, one year after Rumi’s passing. Initially, a cylindrical structure with a turquoise dome was built under the order and supervision of the wife of Emir Suleiman Seljuk, and this structure still stands today. Other sections were added later.

Originally, the mausoleum covered 6,500 square meters, but more than a century later, during the reign of Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II (1481–1512), it was restored and expanded. Today, the complex covers approximately 18,000 square meters.

In 1954, the mausoleum was officially designated as the Mevlana Museum. For decades, visitors from all over the world have traveled to Konya out of love for Rumi. Due to the presence of the great Sufi and mystic Mawlānā Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Balkhī, Konya has become one of Turkey’s major tourist destinations.

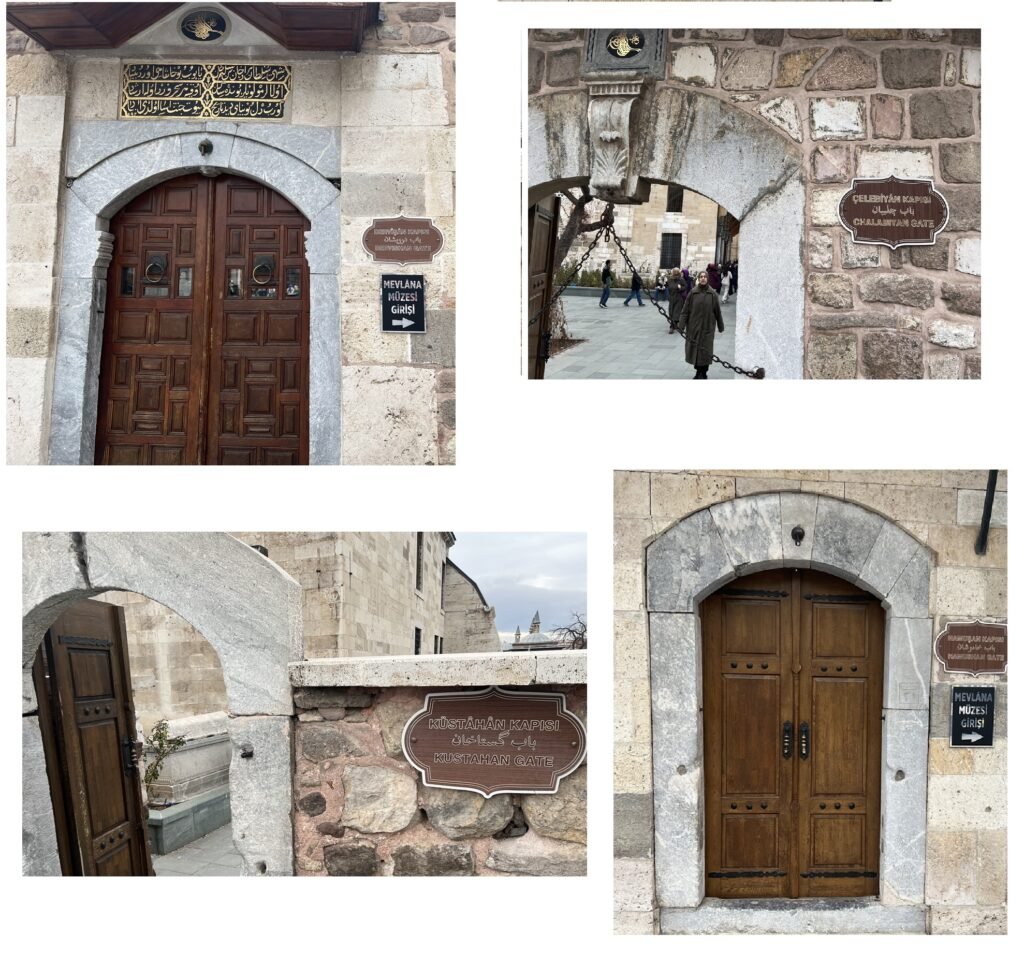

The Main Gates of Rumi’s Mausoleum

Gate of the Dervishes (Bab-e Darvishan):

This was the primary entrance used by dervishes and disciples. It symbolizes entry onto the spiritual path. Traditionally, new initiates (spiritual seekers) entered through this gate at the beginning of their training.

Gate of the Silent Ones (Bab-e Khamushan):

This entrance was mainly used for funeral processions. Khamushan in Persian means “the silent ones,” referring to the deceased. It was regarded as a sacred passage through which souls embarked on their final journey. Even today, it is used during memorial ceremonies.

Silence is considered a virtue among Sufis; a dervish is aware of truths that the general public may not have the capacity to receive. This may be another interpretation of the Gate of the Silent Ones.

Gate of Jalāl:

Reserved for distinguished guests and high-ranking visitors, this gate was used for formal or ceremonial occasions. Its name reflects the divine attribute of Jalāl (majesty or power).

Gate of Jamāl:

Associated with more private or personal visits, this gate was commonly used by worshippers and ordinary visitors. Its name reflects the divine attribute of Jamāl (beauty and grace).

Kushtkhan (Bird House) Gate:

This gate led to the Qushkhaneh (bird house), a special kitchen for preparing food for birds. In the Mevlevi tradition, caring for animals—especially birds—was considered a sacred duty. The gate was connected to the charitable and food-distribution functions of the complex.

It is also associated with the tradition of feeding pigeons, which continues at the mausoleum today. This gate reflects the Mevlevi emphasis on service and compassion toward all living beings. The act of feeding birds was inspired by Rumi’s teachings on kindness to all creation and the spiritual significance of nurturing life.

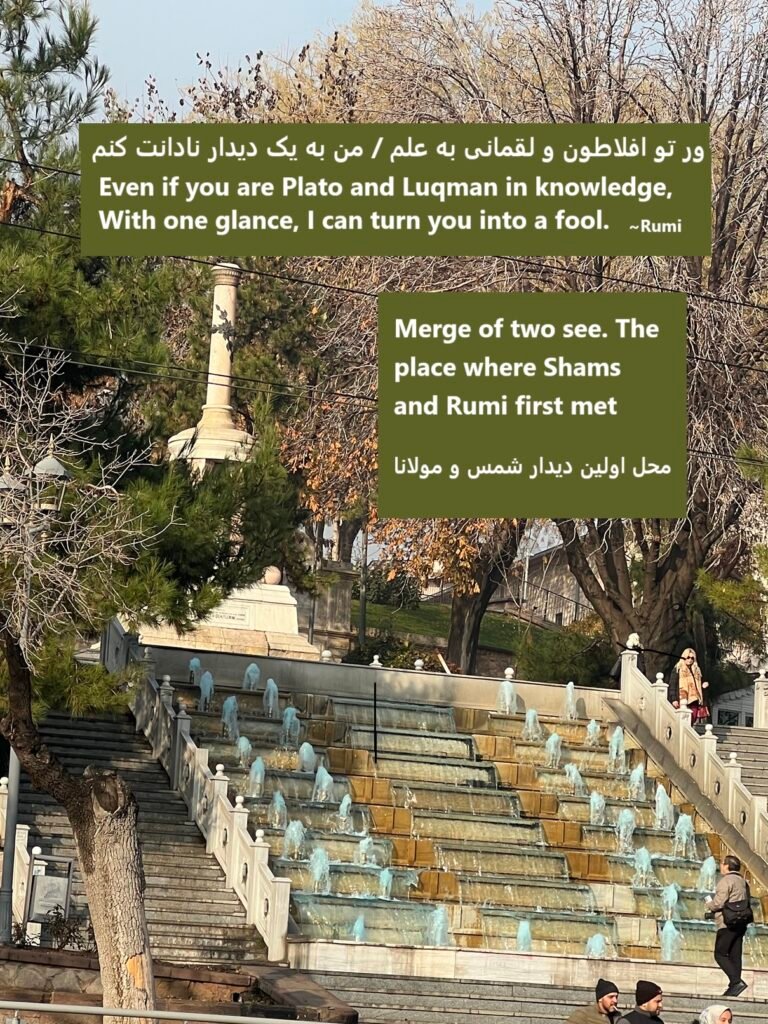

The Site of the First Meeting of Rumi and Shams

Konya, Turkey – 642 AH

The autumn sun was setting over the bazaar of Konya, casting long shadows among the stalls of spice merchants and carpet sellers. Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rumi, a respected scholar and teacher, sat amid his students and a mountain of books. His fingers traced ancient wisdom across the pages, yet in these familiar words he had lately been sensing an indescribable emptiness.

A murmur rose through the crowd. A stranger was approaching—a wandering dervish in a dark cloak, with eyes so luminous that people instinctively stepped aside. This was Shams of Tabriz, though Rumi did not yet know the name that would transform his life.

Shams stopped before Rumi’s gathering. Without greeting or formality, he pointed to the pile of books and asked, “What are these?”

Rumi replied, “These are works of knowledge—though you likely would not understand them.”

Shams smiled—not with offense, but with the knowing smile of one who holds a secret. “You speak of knowledge.” In a swift motion, he lifted the precious volumes and cast them into a nearby pool. The water darkened with ink, as though centuries of learning were dissolving into it.

Rumi rose, his face flushed with anger. “What have you done?”

Calmly Shams said, “These are only words about the Truth. But for one who has never tasted even a drop, what use is speaking of the ocean?”

Before Rumi could respond, Shams reached into the water and drew out the books—completely dry. Not a page was damaged, not a word erased.

Rumi stood astonished. In that moment, something within him shifted—like a key turning in a lock whose existence he had never known. Here stood someone who did not merely study the secret, but lived within it.

Rumi whispered, “Who are you?”

Shams replied, “I am the one you have been seeking, and you are the one for whom I have crossed deserts.”

The bazaar continued in its busy rhythm, but for Rumi and Shams, time stood still. Two souls, destined to ignite one another, after lifetimes of preparation, had finally met. Rumi later wrote:

The Qur’an was always in my hand,

Yet from love I have taken up the lute.

On the tongue that once recited the rosary,

Now there is poetry—couplets, verses, and song.

The students watched in amazement as their revered master, the greatest scholar of Konya, bowed before this strange dervish. They did not know they were witnessing the birth of one of the greatest mystical friendships in history—a meeting that would transform Rumi from a respected scholar into one of the world’s most beloved mystic poets.

Shams extended his hand and said, “Come, and I will show you what lies beyond these books.”

And Rumi, a man who had spent a lifetime teaching others, became a student once more. He took Shams’s hand and left behind his books, his students, and the person he had been until that moment. The sun sank behind the horizon of Konya, marking the end of one life and the beginning of another.

In the years that followed, their bond gave birth to thousands of verses, inspired countless seekers, and revealed the transformative power of divine friendship. But in that first instant, it was simply this: two souls recognizing one another in the crowded marketplace of existence—and having the courage to say “yes” to what that recognition demanded of them.